CELTI. Parte 2°: La scrittura.

La conoscenza che abbiamo del mondo celtico è scarsa. Per molti secoli tra i Celti vigeva il divieto, per motivi religiosi, di scrivere su fatti concernenti la religione ed ogni altra conoscenza ad essa riconducibile, come ad esempio la matematica e l’astronomia. Queste conoscenze furono quindi tramandate per via orale. La scuola per i giovani celti durava almeno 20 anni, il tempo necessario per apprendere e tramandare oralmente. Ciò ha comportato la perdita quasi totale dei loro costumi, conoscenze, credenze.

Mentre dunque la scrittura in Europa risale al III millennio a.C., e popoli come i greci, i cretesi, gli egizi, i fenici, e (in Asia minore) gli eblaiti, i sumeri, gli assiri, i babilonesi lasciavano ampia documentazione scritta della loro civiltà, i Celti si autodistrussero con il loro divieto di scrivere.

Bisogna infatti arrivare al VI sec a.C. per trovare le prime testimonianze scritte “attribuite” ai Celti, dovute all’influenza di fenici, etruschi, greci, latini, iberici.

Persino dopo l’invasione da parte di Roma del mondo celtico, queste popolazioni continuarono a mantenere il divieto di scrittura, fino a quando l’elite intellettuale non si allineò con la cultura del mondo greco-romano. Piano piano il divieto di scrivere venne abbandonato e solo alla fine del II secolo d.C. comparve il primo documento scritto di una delle tradizioni celtiche: il Calendario Gallico. La crescente difficoltà dei Celti di far convivere la loro tradizione con quella romana li indusse a creare questo calendario, di tipo misto: lunare (a scopo religioso e rituale) e solare (a scopo essenzialmente agricolo).

Le iscrizioni celtiche e gli alfabeti usati.

CELTO-ETRUSCO

- ITALIA – Lombardia e Piemonte. Si registrano qui le prime attestazioni di lingua celtica scritta, nell’area della cultura di Golasecca (Golasecca in dialetto è Urasea o Uraseica, dalla radice pre-celtica “our” che significa “acque fluviali”). L’alfabeto usato è quello etrusco. Su un vaso trovato a Sesto Calende, risalente alla fine del VII sec. A.C., si ha la prima attestazione di iscrizione forse in lingua celtica. A Castelletto Ticino è stato ritrovato un graffito di ceramica con iscrizione celtica, proveniente dalla necropoli della zona e risalente alla metà del sec. VI a.C. Nel territorio degli Insubri (la regione compresa tra il fiume Po e i laghi prealpini) sono state ritrovate decine di iscrizioni su vasi risalenti al VI e al V sec. A.C. , nonché monete (dracme padane).

- ITALIA – Umbria: A Todi, in Umbria, è stata ritrovata una stele bilingue celto-latina del II sec. A.C.

- ITALIA – Emilia-Romagna: Ritrovati elmi bronzei con iscrizioni celtiche a Bologna risalenti al III sec. A.C.

- ITALIA – Puglia: Anche in Puglia trovati elmi con iscrizioni celtiche vicino a Canosa.

CELTO-FENICIO

La penisola iberica è stata la seconda regione dell’Europa in cui sono stati ritrovati reperti con iscrizioni celtiche: iscrizioni rupestri, iscrizioni su vasi, diverse stele, monete con nomi di nazioni.

- SPAGNA-Andalusia: Ritrovamenti di una scrittura semi-sillabica di origine fenicia risalente al VII sec a.C.. Nella popolazione si riscontra una componente celtica.

- SPAGNA centrale: E’ solo verso il II – I sec a.C. che tale scrittura mutuata dall’alfabeto fenicio comincia ad essere usata dai gruppi celtofoni della penisola.

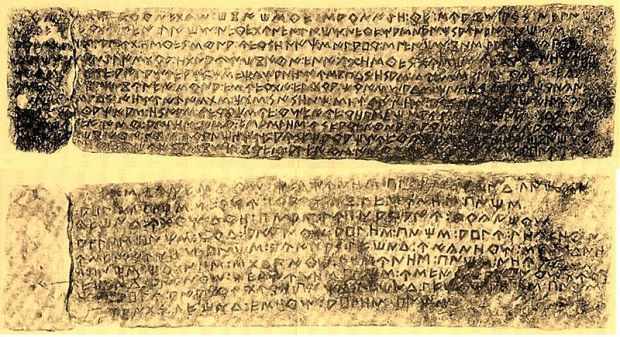

- SPAGNA-Aragona: Vicino Saragozza, nel sito di Contrebia Belasca (presso Botorrita), sono stati ritrovati documenti molto importanti: si tratta di una serie di tavolette di bronzo in lingua celtibera detti “i bronzi di Botorrita”, le cui iscrizioni presentano non una sola parola, ma ben 200-400 parole.

CELTO-GRECO

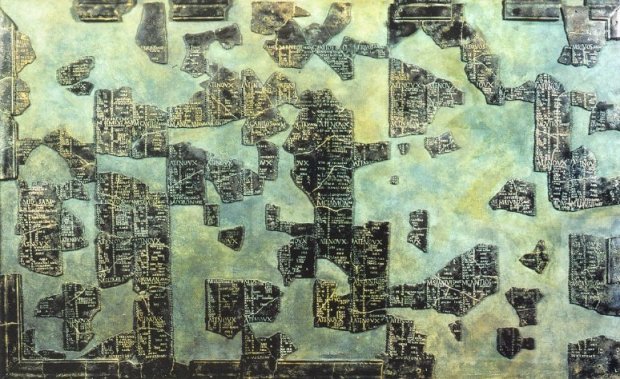

La presenza della colonia greca di Massalia (Marsiglia) determinò probabilmente la diffusione di un alfabeto celto-greco (gallo-greco). Le iscrizioni in lingua gallo-greca sono oltre 70 su pietra, circa 200 su ceramica e una dozzina su materiale vario: oro, argento, piombo e ferro

- Gallia Narbonense: Durante la conquista della Gallia da parte dei Romani, che data dal 150 a.C. in poi, emersero iscrizioni gallo-greche risalenti al III sec a.C. L’uso del gallo-greco si diffuse in tutta la Gallia centrale ed orientale.

- Gallia Elvetica: Iscrizione sulla lama di una spada ritrovata nel sito di Port-Nidau in Svizzera risalente al II sec. a.C. Lo stesso Giulio Cesare racconta nel “De bello Gallico” di aver trovato nel 58 a.C. tavolette di legno in lingua gallo-greco.

- Gallia Bavarese: Un frammento di iscrizione su vaso e altri su ceramica

CELTO-LATINO

Dal I sec a.C. il celto-latino fu certamente l’alfabeto più diffuso (in Europa centrale, nella penisola iberica e anche nella Britannia), a seguito delle conquiste dei Romani. Esso fu usato per trascrivere i testi orali dei celti, tramandati nei secoli, nonché gli unici testi scritti generalmente contenenti elenchi di proprietà di notabili celti. Era diffuso in:

- Pannonia: E’ la parte d’ Europa che oggi comprende parte dell’Austria, l’Ungheria, parte della Croazia e parte della Slovenia. Monete d’argento con nomi di magistrati o notabili.

- Boemia: Cornici ossee per tavolette ignee con iscrizioni, e stiletti metallici

- Gallia centro-orientale: Monete in argento con i nomi di grandi condottieri celti quali Dumnorige e Vercingetorige. E ancora monete con incisi i nomi di popoli o di nazioni

CELTO-OGAMICO

Ultima, in ordine cronologico, a comparire tra i popoli celti, questa lingua merita un cenno a parte. Nata in Irlanda si diffuse essenzialmente nei paesi di origine anglo-sassone (Irlanda, Galles, Scozia, Cornovaglia, Isola di Man). Gli irlandesi, popolo orgoglioso che voleva affrancarsi dal dominio romano, adottarono l’alfabeto latino ma lo criptarono associando ad ogni lettera un simbolo costituito da linee intagliate (in numero variabile da 1 a 5 per ciascuna lettera), posizionate in 4 modi diversi rispetto ad una linea verticale detta “resta” (vedi figura). Si ottenevano così 20 combinazioni per descrivere 20 lettere dell’alfabeto. L’origine di questo sistema di scrittura è da ritrovarsi nell’uso druidico di intagliare il legno (il tasso era un legno venerato) per riti magici di divinazione.

- IRLANDA: Classificate 350 stele in ogamico.

- GRAN BRETAGNA: 50 stele, nonché stele bilingui (in ogamico e in latino)

Libri consigliati: Venceslas Kruta: La grande storia dei Celti

Le immagini che seguono sono frutto di ricerche su Internet.

Fig 051 – Alfabeto insubre derivato dall’etrusco (tav. Brandolini) – Insubrian alphabet originated fron etruscan

Fig 122 – Spagna, Botorrita – Tavoletta di bronzo (fronte-retro) – Bronze tablet from Botorrita in Spain (front & back)

The images are the result of research on Internet

CELTS. Part 2: Writing.

Our knowledge of the Celtic world is very poor.

For many centuries among the Celts there was the ban for religious reasons, to write about facts concerning religion and any other knowledge attributable to it, such as mathematics and astronomy. This knowledge was then passed down orally. The school for young Celts lasted at least 20 years, the time required to learn and pass on orally. This led to the almost total loss of their customs, knowledge, beliefs.

While writing in Europe dates back to the III millennium BC, and people like the Greeks, the Cretans, the Egyptians, the Phoenicians, and (in Asia Minor) the Eblaites, the Sumerians, Assyrians, Babylonians left a large written documentation of their civilizations, the Celts destroyed themselves with their ban on write.

We must therefore go on to the VI century BC in order to find the first written “attributed” to Celts, due to the influence of the Phoenicians, Etruscans, Greeks, Romans, Iberians.

Even after the invasion by Rome of the Celtic world, these people continued to maintain the prohibition on writing until the intellectuals lined up to the greek-roman culture. Slowly the prohibition of writing was abandoned and only at the end of the second century AD appeared the first written document of one of the Celtic traditions: the Gallic Calendar. The increasing difficulty of the Celts to reconcile their tradition with the Roman led them to create this calendar, mixed type: lunar (religious and ritual purposes) and solar (mainly agricultural purposes).

The Celtic inscriptions and the alphabets they used.

Celtic-Etruscan

• ITALY – Lombardy and Piedmont. We record here the first evidence of Celtic written language, in the area of culture of Golasecca (Urasea or Uraseica, in the local dialect, from the pre-Celtic root “our” meaning “river water”). The alphabet used is the Etruscan. On a vase found in Sesto Calende, dating from the late seventh century AC, we have perhaps the first attestation in the Celtic language. In Castelletto Ticino was found a graffito ceramic with celtic inscription, coming from the necropolis in the area dating back to the VI century BC . Within the territory of Insubri (the region between the river Po and the alpine lakes) have been found dozens of inscriptions on vases dating from the VI and V century A.C. , as well as coins (drachmas of Po river valley).

• ITALY – Umbria. In Todi was found a bilingual stele Celtic-Latin of the II century A.C.

• ITALY – Emilia-Romagna. In Bologna bronze helmets with Celtic inscriptions dating to the III century A.C.

• ITALY – Puglia. Near Canosa found Celtic helmets with inscriptions.

Celtic-Phoenician

The Iberian Peninsula was the second region of Europe where artifacts were found with celtic inscriptions: rock inscriptions, inscriptions on vessels, several steles, coins with the names of nations.

• Spain-Andalusia: Findings of a semi-syllabic writing of Phoenician origin dates back to the VII century BC. In the population there is a celtic component.

• Central Spain: In the II century BC Celtic-Phoenician writing, loaned from the Phoenician alphabet started to be used by the groups of celtic language in the peninsula.

• Spain-Aragon: Near Zaragoza near, in the site of Contrebia Belasca (at Botorrita) have been found very important documents: a series of bronze tablets in celtic language called “Botorrita bronzes”, whose inscriptions are not the usual single word, but as many as 200-400 words.

Celtic-Greek

The presence of the greek colony of Massalia (Marseille) is probably the origin of the diffusion of a Celtic-greek (Gallo-greek) alphabet. The Gallo-Greek inscriptions are more than 70 on stone, about 200 on ceramics and a dozen of various materials: gold, silver, lead and iron.

• Narbonne Gaul: During the conquest of Gaul by the Romans, which dates from 150 BC onwards, emerged Gallo-Greek inscriptions dating to the III century BC The use of the Gallo-greek spread throughout the central and eastern Gaul.

• Swiss Gaul: Inscription on the blade of a sword found in the site of Port-Nidau in Switzerland dating from the II century. B.C. Julius Caesar himself says in “De bello Gallico” he had found in 58 BC wooden tablets in Gallo-greek language.

• Bavarian Gaul: A fragment of inscription on pottery vase and other objects.

Celtic-Latin

From the I century BC the Celtic-Latin alphabet was certainly the most popular (in Central Europe, the Iberian Peninsula and also in Britain), due to the conquests of the Romans. It was used to transcribe the spoken texts of the Celts, handed down over the centuries, and the only written texts generally containing property lists of notables Celts. Was widespread in:

• Pannonia: Pannonia was that part of Europe which now includes part of Austria, Hungary, part of Croatia and Slovenia. Silver coins with the names of magistrates or elders have been found there.

• Bohemia: Frames (made of bones) for igneous tablets with inscriptions, and metal stilettos.

• Central and Eastern Gaul: Coins in silver with the names of great leaders such as Celtic Dumnorix and Vercingetorix. And more coins inscribed with the names of peoples or nations

Celtic-Oghamic

Last, in chronological order, to appear among the Celtic peoples, this language deserves a special mention. Born in Ireland, became widespread mainly in the Anglo-Saxon countries (Ireland, Wales, Scotland, Cornwall, Isle of Man). The Irish, proud people who wanted to free themselves from Roman domination, adopted the Latin alphabet but they encrypted it, associating to each letter a symbol consisting of scored lines (varying in number from 1 to 5 for each letter), placed in 4 different ways on a vertical line (see figure), resulting in 20 combinations to describe 20 letters of the alphabet. This writing system has its origin in the use of Druids of wood carving for magical rites of divination (the yew tree was revered by the Celts).

• IRELAND: 350 oghamic steles.

• GREAT BRITAIN: 50 steles, and also bilingual steles in oghamic and Latin

Recommended books: Venceslas Kruta: Les Celts, Histoire et dictionnaire

Devi effettuare l'accesso per postare un commento.